Every one of us started out as a single cell, dividing into two, then three and four cells during the first two days after fertilization. But only a few early embryos – about one in three – have a genetic makeup that’s good enough to let them continue their development. Scientists don’t know why, but together with cheetahs and horses, we humans are some of the least fertile mammals around.

About 10 to 15 percent of couples have trouble conceiving. Among them, some end up needing in vitro fertilization (IVF), a treatment in which doctors join a woman’s eggs with a man’s sperm in the lab, in hopes of creating several healthy embryos that they can transfer into a woman’s uterus.

For IVF patients, any information on which of their embryos has the best chance of growing into a baby is invaluable. Because several embryos are often transferred, in vitro fertilization patients who get pregnant have much higher rates of twin and triplet pregnancies than the general population. These pregnancies can be risky for the mother and the babies.

And many IVF patients don’t get pregnant at all. According to the Centers for Disease Control, only 46 percent of embryo transfers culminate with a birth. And that’s among women under 35, who have a better chance of getting pregnant than older women.

Auxogyn, a company in Menlo Park, has developed a test that company officials say can help with this problem. The so-called Eeva Test was cleared by the FDA in 2014 and is already being used in more than 30 fertility clinics, said Alice Chen, Auxogyn’s director of biomedical research.

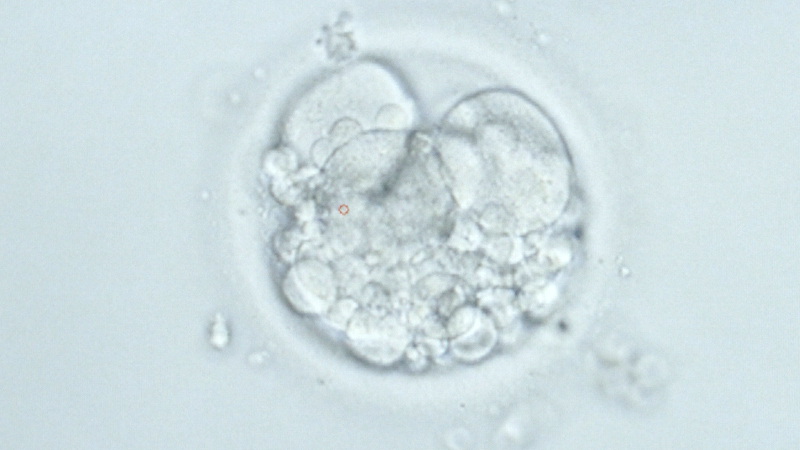

The test’s goal is to help embryologists at fertility clinics pick out the early embryos with the best chance of making it to day five, a critical milestone. On the fifth day after fertilization, the embryo has about 200 cells and is getting ready to break out of its shell, a dramatic event that allows it to then burrow into the uterus and continue its growth.

“If an embryo reaches day five, it has an increased chance of implanting and growing into a live baby,” said Chen.

The Eeva Test is the result of a key finding about embryo development made at Stanford University in 2010. By examining time-lapse videos of developing embryos, scientists there discovered that the embryos that made it to day five had actually followed a precisely timed pattern, something like an embryonic clock.

“There are strict parameters around normal development,” said Renee Reijo Pera, the scientist who led the Stanford research. “An embryo can’t spend the first couple of days without making progress or else it won’t have the right structure to attach to the uterus. It really, really, really matters.”

Up until then, researchers – including Reijo Pera – thought that embryos could grow at many different rates and still be healthy. But her research, and subsequent studies by Auxogyn, have shown that embryos that divide from two to three cells in nine to 11 hours, and then from three to four cells in under two hours, have the best chance of making it to day five.

“The timings can’t be too fast or too slow,” said Chen. “When the timings are just right, those embryos have a higher chance of developing to day five.”

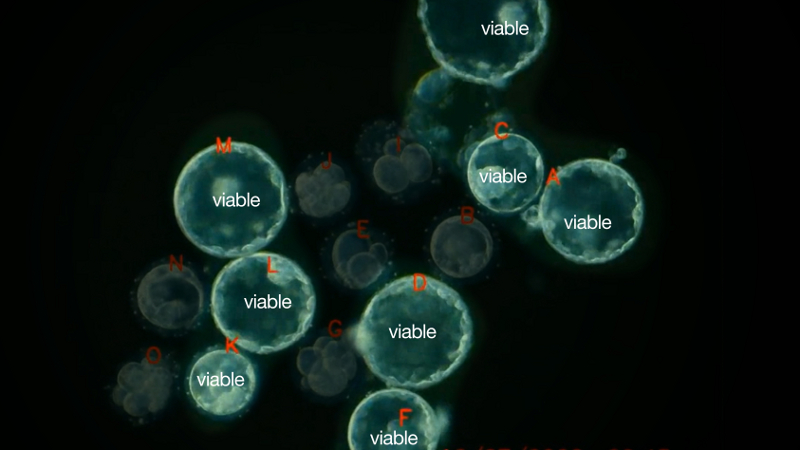

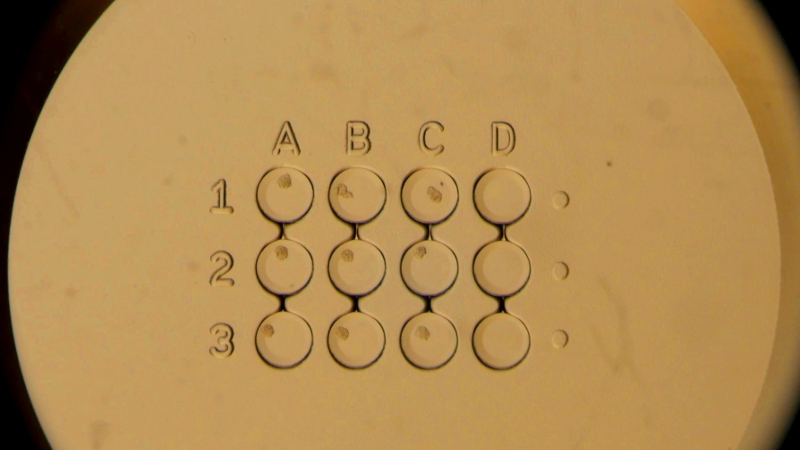

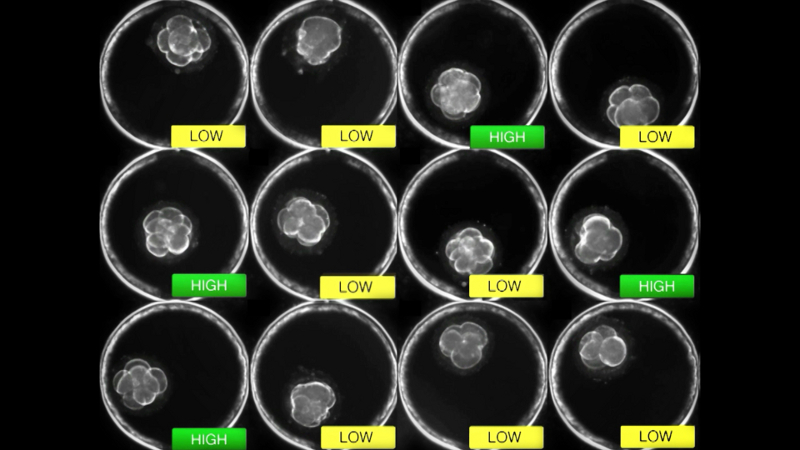

Auxogyn developed the Eeva Test based on this knowledge. In the test, embryos – which at this point are one and a half times the width of a human hair – are placed inside tiny wells in a petri dish. The dish is then placed under a microscope that goes inside the incubator. A tiny camera in the microscope takes photos of the embryos every five minutes as they divide and develop.

Using this time-lapse video, a computer algorithm automatically tracks the development of each embryo. The software gives a “high” grade to the embryos that most closely followed the pattern identified by the Stanford team. The embryos that deviated the most from the pattern get a “low” grade. This information helps embryologists select day three embryos with a higher chance of growing to day five.

“It was important that the system be automated and amenable to complement what embryologists are already doing,” said Reijo Pera, who now works as vice president for research at Montana State University.

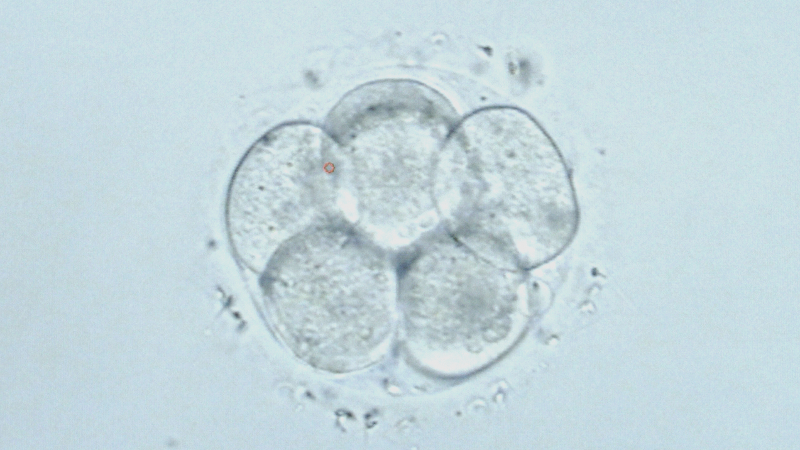

Embryologists at fertility clinics traditionally have graded embryos by looking at them under a microscope three days after fertilization, when they look like a tiny clump of grapes. They look for embryos with six to 10 cells of the same size. But that system has shortcomings.

“If they have a group of decent-looking embryos, it’s hard to decide which ones have the best chance,” said Chen. “That’s where the Eeva information is most useful.”

The test allows clinics to transfer one or two three-day-old embryos with the best chance of reaching day five. The test is part of an effort among fertility doctors that started in the late 1990s to bring down the rate of multiple pregnancies among IVF patients. In 2011, doctors transferred an average of two to three embryos, according to the CDC, and about one woman in 100 who got pregnant through IVF in the US ended up having triplets. Naturally, triplets occur in about one in 10,000 pregnancies.

“There’s an international effort to move towards single embryo transfers,” said Kelly Athayde Wirka, an embryologist at Auxogyn.

Author’s note: We received a question as to whether any data has shown that the Eeva Test leads to an increase in live births among IVF patients. No research results to date show that the test increases the rate of live births among patients. Auxogyn’s Alice Chen said that the company is collecting data on this question.